On the 18th of April 1968, listeners to BBC Radio 4’s breakfast programme, Today, could perhaps be forgiven for choking on their toast. For that morning, the nation heard an American businessman announce that his company had just bought London Bridge.

Not only that, but this SE1 landmark was to be transported several thousand miles to Arizona where it would initially be re-erected, piece by piece, over an arid patch of desert sand. Even now, standing on Borough High Street amid the bustle of traffic, with the otherworldly Shard unavoidably in sight, this story seems no less bizarre. And yet, this extraordinary deal, the selling of what The Guinness Book of Records celebrated as “The World’s Largest Antique”, was clinched over 45 years ago.

London Bridge’s unlikely journey from rain-drenched Southwark to dust-dry Mojave County, USA, began in 1967. It was then that Ivan Luckin, a former Daily Telegraph journalist and public relations agent turned City politician, persuaded the Corporation of London to put it on the market. The bridge had been fashioned for posterity in 130,000 tons of granite in 1831 by the great Scottish engineer John Rennie. By the early 1960s, however, it was calculated to be sinking into the Thames river bed at a rate of an eighth of an inch a year. Car ownership was also then rising sharply. The bridge, designed when London was still untroubled by the horse-drawn omnibus, was deemed embarrassingly out of date.

This was the Swinging Sixties, the era when Philip Hardwick’s Doric Arch at the entrance to Euston station was needlessly destroyed and most of its stonework dumped into the river Lea. The Coal Exchange on Lower Thames Street, a prime example of an early Victorian cast iron building, was junked in a road widening scheme. And plans to erect a series of motorways across London, eviscerating historic areas like Greenwich and Covent Garden, were in motion. Accordingly, the replacement for Rennie’s London Bridge, which serves the capital to this day, was built in reinforced concrete. Structurally it has far more in common with the Westway flyover than neighbouring Thames crossings like Southwark or Blackfriars.

And yet, discontent about the pace of change in London had been growing. In part, this was bolstered by the successful campaign to save Gilbert Scott’s high gothic St Pancras Station from demolition led by the poet John Betjeman. St Pancras was listed in 1967 and London Bridge’s auction, opened that same year, was, in fact, marketed as an act of preservation. An official press release from the Corporation of London calling for potential bids stated that it would not be “worthy for a great historic monument to be broken up” or “sold little by little”.

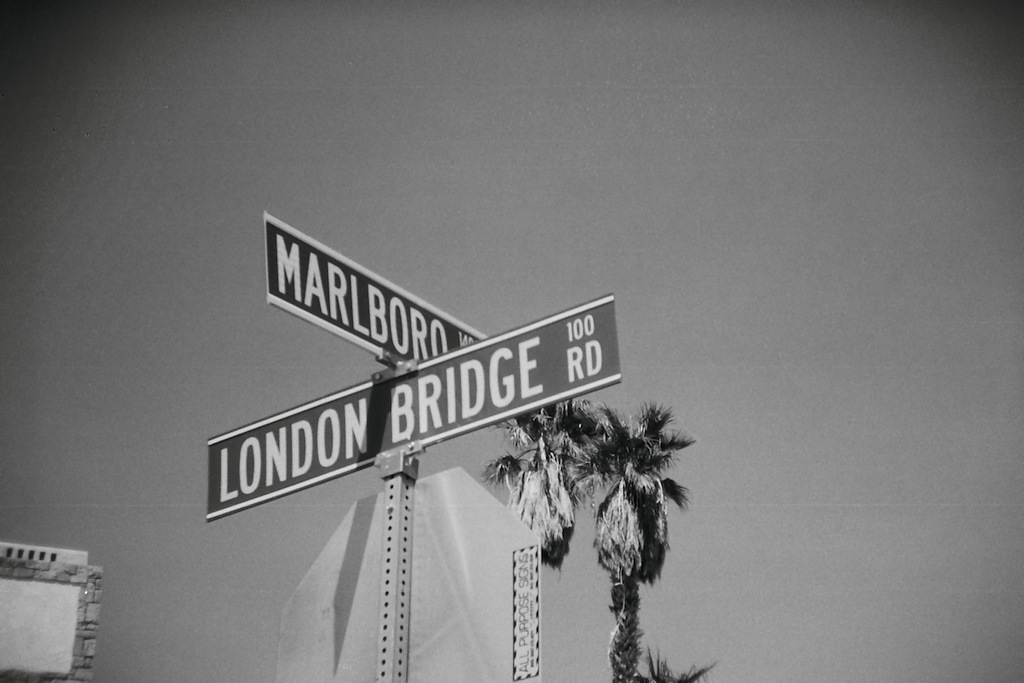

Its eventual purchasers were the McCulloch Corporation from America, run by Robert P McCulloch and CV Wood. McCulloch was a flamboyant millionaire oil baron, real estate speculator and chainsaw magnate. In 1963, he had hatched a scheme to build a new city at Lake Havasu beside the Colorado River in Arizona, where he already had outboard motor testing facility. The idea of buying London Bridge at a cost of $2,460,000 (£1,029,400 – 10s 4 ½ d old money), came from Wood, his business partner. Previously the planner behind Disneyland, Wood felt it would put Lake Havasu City on the map. He was proved right. The self-styled “home of London Bridge” currently has over 53,000 residents. Those numbers bolstered every winter with the arrival seasonal retirees known as “snow birds”. In turn, each March and April they are replaced by thousands of college students, the infamously hedonistic “spring breakers” as depicted in Harmony Korine’s recent film, who flock there to party on the lake.

Back in 1968, many in London felt that converting a working bridge into the centrepiece of a custom made resort, one that for several decades was to boast an ersatz traditional English pub and a double-decker bus serving as an ice cream parlour, was an ignominious fate for such a structure. A structure, after all, that had previously been immortalised by T S Eliot in The Waste Land. John Jennings, the Conservative MP for Burton, demanded that the Labour government take steps to “prevent the sale of London Bridge to interests in a foreign country”. But it was to no avail, and its departure was subsequently mourned in pop songs by Cilla Black and the band, Bread.

Still today, all along the South Bank, numerous formally defunct wharfs, warehouses, factories and power stations can be found happily enjoying second lives as shopping centres, theatres or art galleries – from Hays Galleria off Tooley Street and the Menier Chocolate Factory on Southwark Street to, of course, the Tate Modern gallery on Bankside. This repurposing of old industrial buildings is so ubiquitous we rarely comment on it. But the sale and transplanting of London Bridge to America, if a rather elaborate example, was arguably at the forefront of this trend.

And, close to half a century after the sale was agreed, London Bridge in America, like its successor in the city, shows no sign of falling down.